|

The image above provides a visual illustration of a Marxist

view of Tsarist Russia, one in which soldiers and sailors and other lower-class

members were the foundations of the society, despite this they lacked rights

and were exploited by those above them. They had no vote or say in national

politics, but they had still been fighting a war in the name of it since 1914.

The February and October Revolutions of 1917 changed all this. The

lower-classes were exposed to new possibilities and new ideas of revolution and

freedom which were being offered to them by the political opponents of Tsarism.

As Wade puts it, ‘The February Revolution

had transformed the formerly submissive soldiers and sailors into a

self-conscious political force with their own aspirations and organization.’² The war continued to consume their lives and was the cause

for a lot of suffering in the front and the rear. The general outlook the

soldiers and sailors had was influenced by the war and the revolutionary ideas

that emerged after February; these things motivated their military conduct

during both revolutions in which they decided whether or not to support change.

By analysing the letters and resolutions written in 1917 one

can see how the soldiers and sailors viewed their situation. Documentation like

reports and appeals written by authority figures will also be studied to get an

impression of the more general trends emerging at the time. The voices of all

soldiers will not be heard in these written documents because only those who

had a direct agenda would bother to write to authority figures or appeal to groups.³ Modern historians like Ashworth, Ferro, Wade and Wildman all

appreciate the importance of both factors in stimulating the behaviour of military

personnel. Their arguments and studies will be referred to in order to provide

this discussion with in-depth research that will put these documents into a

wider historical context which should help in determining their significance.

The February Revolution came as a result of a spontaneous

uprising by the Petrograd workers, which the Petrograd garrison refused to put

down and later joined which forced Tsar Nicolas II to abdicate. Ashworth rejects traditional Marxist arguments

that suggest that the Petrograd garrison had political motivations based around

class consciousness when they decided to support the uprising. Instead he convincingly

argues that they saw this as a chance to express their war weary feelings by

not supporting the regime that got them into the war, therefore securing a

change of leadership and offering their loyalty to any group who would improve

their military situation.⁴ This was certainly the view of this

soldier, who wrote to the Soviet saying, ‘for

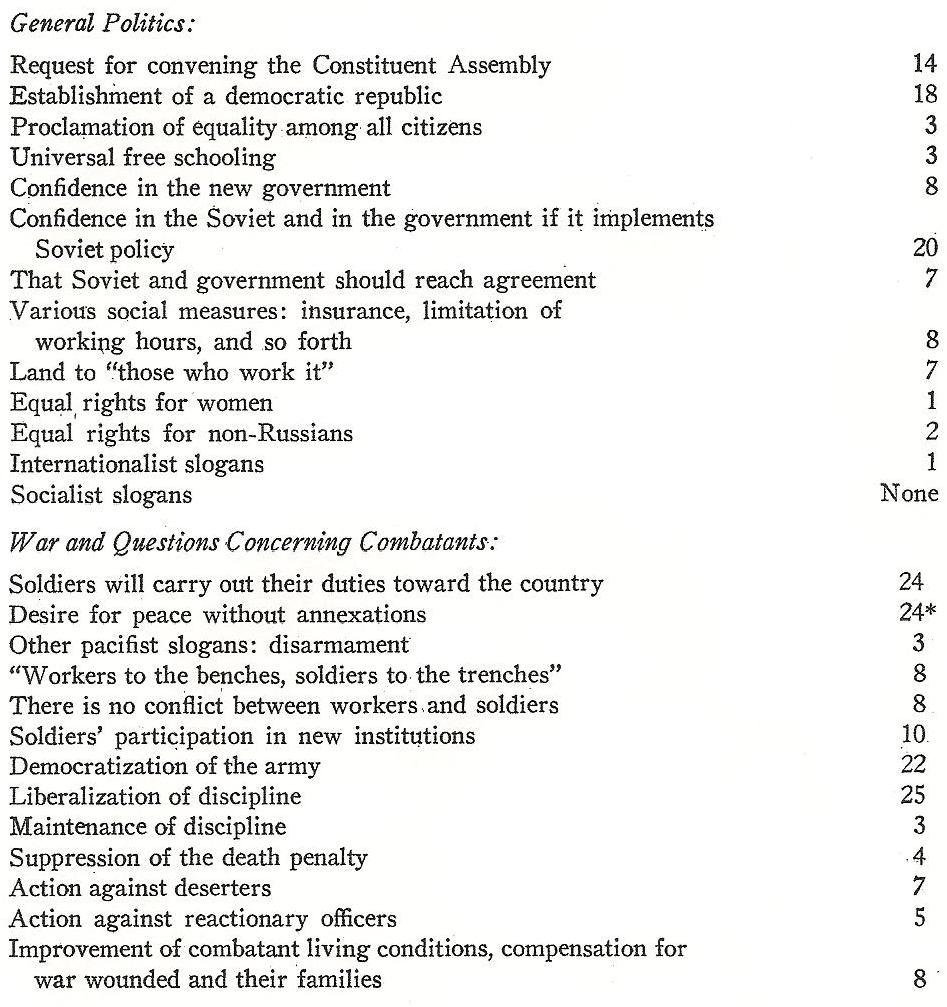

the troops a change in regime betokened the end of the war.’⁵ As the table

below shows many soldiers did support the setup of democratic institutions from

the start which is probably more of a means of bringing military change as can

be seen in the number of resolutions regarding the war and military discipline.

Only a minority of soldiers are concerned with the need for a social revolution

involving greater equality, education and land redistribution, which were major

concerns for non-combatants.

|

The reason for such limited political vision was because most

soldiers lacked experience in political affairs due to the fact they were

forbidden from joining political parties and demonstrations and until Order No

1 had no organization looking out for their interests. It is little surprise

that with their new democratic freedoms they were uncertain what to do with it,

with some soldiers asking the government to enlighten them on political

matters:

‘Now the chains have been broken and we are

now free, yet we remain as ignorant and helpless as ever. Before long there

will be a Constituent Assembly. We do not want to be mute and passive voters

and deputies. We want to know what this or that form of rule holds in store or

us.’⁷

It is highly unlikely that soldiers were influenced by

revolutionary ideologies when they decided to support the February Revolution

due to the limited amount of political knowledge they possessed, whereas they

were all weary of war and were willing to support the February Revolution in

order to end it.

Soldiers began to realise peace could not be declared

immediately, because the Central Powers would be determined annex Russian

lands. Appeals were made to armies to stay at their posts in order to defend

Russia, ‘We will not disgrace

ourselves by ceding our freedom, our happiness, to the enemy. Now we are

expecting you to make an all-out effort for the defence.’⁸ The soldiers could appreciate this, they had acquired new freedoms

of being able to vote for representatives in military committees and local

Soviets to protect their interests and they realised that defeat to the

autocratic Central Powers could result in Russia losing more than land. They

did not wish to fight anymore but they did not want the last three years of

suffering to be for nothing, so many felt compelled to defend Russia and their

own liberties.⁹ It is for this reason that Order No

1 tries defend both self-discipline and liberty:

‘In

the ranks and during their performance of the duties of the service, soldiers

must observe the strictest military discipline, but outside the service and the

ranks, in their political, general civic, and private life, soldiers cannot in

any way be deprived of those rights which all citizens enjoy.’¹⁰

Soldiers agreed to follow this order, especially as it

coincided with the policy put forward by Tsereteli of ‘Revolutionary

Defencism’. This policy was popular with soldiers because the ultimate goal was

establishing a peace that preserved Russia and the revolutionary liberties of

the people and until that time troops would only have to defend Russia, they

would not have to risk their lives to expand her.¹¹ This suited the demands of military

men perfectly, who saw no point in offensive manoeuvres, like the soldiers serving

under Fedor Stepun who responded to aggressive orders from the General Staff by

saying, ‘ “What the devil do we need

another Hilltop for, when we can make peace at the bottom?”’¹² This consensus was maintained for several

months in which most troops stuck or returned to their posts so they would not

betray their country and rights to the enemy.¹³

However

no matter how well the war went or however much soldiers saw it as their duty; the

war still drained their energy. Soldiers did choose to stay at their posts but

only because they feared the implications if they lost.¹⁴ Over the year

soldiers began to wonder if it was really worth it, soldiers appealed to

Kerensky in August feeling that defeat was inevitable anyway so why prolong the

suffering, ‘... put an end to the slaughter. Only by

doing this can you keep the enemy from penetrating deep inside Russia and save

us both from this invasion and from starvation.’¹⁵ Reports suggest that such desires to not fight were pretty

widespread by October and had resulted in a decline in discipline and a rise in

desertion. Orders were being disobeyed; on the Western front there was an

incident in which, ‘over eight-thousand

soldiers who were to be transferred to the front demanded to be sent home

instead.’¹⁶ In the rear in places like Stavka order seemed to have

completely deteriorated, ‘Drunken

soldiers are rioting and shooting at their fellow soldiers.’¹⁷

Disorder

and discontent was definitely spreading throughout Russia between February and

October. However many remained at their posts and while military committees made

louder demands for a speedy peace it would be ‘peace without annexations or indemnities’. This meant it would

take a while as Russia would need to make agreements with the enemy in which

Russia would stop fighting but would lose nothing. Committees realised that

they needed, ‘to supply the army with all

necessities... since the demobilization can proceed only gradually.’¹⁸ Many

realised they had a duty to defend Russia still, however many were becoming

weary of the revolutionary government, military men including those who wrote

the resolution above were becoming less confident about serving under them

saying, ‘The indecisive policy of the

government is accelerating the crisis.’

It

was the soldiers and sailors who had secured the February Revolution and they

realised this, one resolution states that the authority of their leaders

depended on them and, ‘If they do not yield to the people, the

people must sweep them aside with one mighty motion.’¹⁹ Because of this and the fact the Provisional government only

had executive powers it had to create policies which the people liked or accepted

in order for them to be carried out by the people.²⁰ The government did struggle to enforce its will on people

because they lacked coercive state organs. For instance military officers

usually had to comply with the demands of their men in order to make them obey

orders, for instance General Vertsinsky liberalized army conditions in

accordance with Order No 1 saying, ‘...introducing

inevitable changes in the life of the corps, it helped to prevent the wild

excesses which took place elsewhere.’²¹

‘Wild excesses’, is a reference to the

removal of more conservative military officers from their posts, such as the murdered

and deposed Kronstadt officers who had tried to prevent revolutionary change affecting

their base in February.²² Despite attempts of several ministers and officers to

win the favour of the lower-orders, the view the soldiers and sailors had of

these groups deteriorated over the year. There had often been mistrust for

officers amongst the lower-orders due to their links to the Tsarist past and their

attempts to restore obedience, however by September such views had escalated, ‘We cannot defend the country under the

command of the general staff. We don’t trust them anymore. We see them as

blatant counterrevolutionaries...’²³ Such extremities even resulted in the murder

of senior officers later in the year in places like Vyborg, one witness

understood the reason for this, ‘I am aware that they wanted to crush

Kornilov’s lackeys and weaken them, but no one will achieve anything doing it

this way.’²⁴ It is true that mistrust of senior

officers had been mounting over the summer months due to attempts to

reintroduce coercive measures to army discipline like capital punishment, and

once General Kornilov attempted to march on Petrograd the lower-orders could no

longer tolerate them- they were counterrevolutionaries.

Even

after the demonstrations against them during the July Days, the Provisional

Government continued to have the ‘unconditional confidence’ of some soldiers

who believed they still embodied the revolutionary ideologies of February and

felt they were still capable of bringing liberty, equality and fraternity to

Russia.²⁵ However the government made some catastrophic decisions such as

ordering an offensive against the enemy in June. Many soldiers refused to obey,

‘We must end the war no matter what, and

if they want an offensive, then we’ll mount an offensive against the

capitalists and the bourgeois that are drowning us and killing us and our

freedom.’²⁶ An offensive went against the will of many soldiers which is

why many avoided it, while those who did were routed by the enemy leaving the survivors

disillusioned with the government due to them increasing their war suffering.²⁷

The government also tried to provide more order to society and the military in

the summer by reintroducing harsh criminal punishments like the death-penalty

for soldiers, which greatly angered them as it seemed their February gains were

being abandoned, ‘The

rights of the soldier are falling by the wayside, so is the reinforcement of

the rights of freedom, and in their place Articles 129 and 131 are being

advanced once again.’²⁸

It was during these months that Bolshevism was able to

influence the revolutionary ideologies of soldiers. The Bolsheviks championed

their struggle, saying they could provide the desired peace and rights which

the Provisional Government had failed to do. In doing so the Bolsheviks were

able to politicise military men by saying the war was an ‘imperialist war owing to the capitalist nature of the government’ and

was not in their proletarian interests.²⁹ The

Bolsheviks promoted the notion that the bourgeois government and General Staff

were counterrevolutionaries who were retreating from revolutionary rights so

they could restore discipline and order, vindicating their point by referring

to the offensive, conservative policies and Kornilov Affair.³⁰ The Provisional Government was failing the desires of the military

men and as a result many were persuaded into following more radical policies ‘... the provisional government promised

during the first days to give the poor people their freedom but they didn’t. We

are little by little going over entirely to the side of the Bolsheviks.’³¹ ‘All Power to the Soviets’ was a revolutionary

ideology the Bolsheviks endorsed which also pleased the lower-orders, for the

Soviet was held in high-esteem by them due to the fact they were elected to

represent their interests.³² By October many military men had lost all enthusiasm for the Provisional

Government, many committees now wrote resolutions supporting the seizer of

power by the Soviets as a way of representing popular opinions , ‘We consider the All-Russian Congress of

Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’, and Peasant’s Deputies to be the sole organ

reflecting the will and voice of the people.’³³

|

The results from the Constituent Assembly show how dominant

socialist ideas amongst military men were by the end of 1917, with both the

Social-Revolutionaries and Bolsheviks earning around 40% of their vote each.

Both parties upheld the political and social revolutionary ideologies the

military men shared such as democratizing military service, redistributing the

land, transferring power to the Soviets and seeking peace. The Bolsheviks were

able to topple the Provisional Government in October not because they were the

most popular party but due to the fact the Provisional Government lacked any

mass support, while the lower-classes at least sympathised with the decisive

action of the Bolsheviks to remove obstacles of the socialist revolution and

therefore allowed this revolutionary vanguard to seize power unheeded.³⁶ This was certainly the view of some soldiers like those of

the Electrotechnical Battalion who stated in a resolution, ‘We declare that we are not all Bolsheviks, all of us stand as one for

the unified program of actions and will follow without hesitation this party,

which will move decisively and relentlessly toward the stated goal of total

emancipation for all labourers.’³⁷

In February war weariness made the military men of Russia

feel that they could no longer live under Tsarism and by refusing to comply

anymore they were able force Nicolas to abdicate. The democratic revolution

changed the way the people viewed their government; leaders now had to prove

their legitimacy to the people or else be removed by them. Military men

embraced revolutionary ideologies, at first this universally included political

desires to be treated as sovereign citizens. Later on a significant number of

them had increasingly radical views about bringing a socialist revolution to

Russia which involved policies like redistributing land and vesting all power

to the Soviets. However the Provisional Government failed to implement such

revolutionary ideas, instead seeming to adopt conservative values due to

influence from the General Staff and bourgeoisie. The masses were all opposed

with a return to Tsarism and military men either began to lose faith in the government

or regarded them as counterrevolutionaries. The Bolsheviks were greatly

influential in exposing the lack of popular legitimacy in government actions to

military men, losing the government the popular, military support it

desperately needed in order to run the war and country. Lenin politically radicalised

many military men by showing them that this imperialistic war they were sacrificing

their lives for was not to their benefit and the ultimate example of bourgeois

exploitation. This helped create open hostility to the leaders, officers and

bourgeoisie; because this asserted that they were only interested in their own

prosperity and glory and not the popular desires for revolution and peace.

Endnotes

1. A.Radakov,

‘The Autocratic System (1917)’, Seventeen Moments in History, www.soviethistory.org (6 December 2010)

2. R.Wade, The Russian Revolution, 1917 (London, 2003), p.111

3. M.D.Steinberg, Voices of revolution, 1917 (New Haven, 2001), p.3

4. T.Ashworth, ‘Soldiers not Peasants: The Moral basis of the

February Revolution of 1917’, Sociology,

26 (1992), p.468

5. ’Revoliutsionnoe dvizhenie v rossii posle sverzheniia samoderzhaviiad’,

in M.Ferro, ‘The Russian Soldier in 1917:

Patriotic, Undisciplined and Revolutionary’, Slavic Review

30 (1971), p.491

6. M.Ferro, ‘The Russian Soldier in 1917:

Patriotic, Undisciplined and Revolutionary’, Slavic Review

30 (1971), p.512

7. Document 27 in M.D. Steinberg (ed.), Voices of Revolution, 1917 (New Haven,

2001), pp. 114-115

8. Document 23 in Steinberg , Voices, pp. 107-8

9. Ferro,

‘Russian Soldier’, p.492

10. ‘‘Order No.1’, 1 March 1917 (14 March

1917)’,Seventeen Moments in History, www.soviethistory.org (6 December 2010).

11. Wade, Russian Revolution, pp.67-73

12. F.Stepun, ‘Byvshee i nebyvsbeesya’, in A.K.Wildman, ‘The

February Revolution in the Russian Army’, Soviet

Studies, 22 (1970),

p.10

13. A.K.Wildman, ‘The February Revolution in the Russian Army’, Soviet Studies, 22 (1970), p.17

14. Steinberg, Voices, p.50

15. Document 78 in Steinberg , Voices, p. 218

16. ‘Army

Intelligence Report for September 19-30 (13 October 1917)’, Seventeen Moments in History, www.soviethistory.org (6 December 2010).

17. ‘Petrograd

Telegraph Agency, Condition of the Troops In the Rear (1917)’, Seventeen Moments in History, www.soviethistory.org (6 December 2010).

18. Kozhevnikov,

‘Resolution of the Army Committee of the Western Front. October, 30 1917 (12

November 1917)’, Seventeen Moments in

History, www.soviethistory.org (6

December 2010).

19. Document 81 in Steinberg , Voices, pp. 220-225

20. Wade, Russian Revolution, pp.56-7

21. E.A. Vertsinsky, ‘God revolyutsii’, in A.K.Wildman, ‘The

February Revolution in the Russian Army’, Soviet

Studies, 22 (1970),

p.22

22. D.A.Longley, ‘Officers and Men: A Study of the

Development of Political Attitudes among the Sailors of the Baltic Fleet in

1917’, Soviet Studies 25 (1973), pp. 29-30

23. Document 81 in Steinberg , Voices, pp. 220-225

24. Document 80 in Steinberg , Voices, p. 219

25. Document 69 in Steinberg , Voices, pp. 201-202

26. Document 33 in Steinberg , Voices, p.122

27. Wade, Russian Revolution, pp.182-3

28. Document 36 in Steinberg , Voices, pp.122-3

29. V.Lenin,

‘The Task of the Proletariat in the Present Revolution. April 4,1917 (17 April

1917)’, Seventeen Moments in History, www.soviethistory.org (6 December 2010).

30. Wade, Russian Revolution, pp.206-9

31. Document 75 in Steinberg , Voices, p.213-4

32. Wade, Russian Revolution, p.209

33. Document 87 in Steinberg , Voices, p.232

34. L.Protasov, ‘The All-Russia

Constituent Assembly and the Democratic Alternative’, in R.Wade, Revolutionary Russia: New Approaches

(London, 2004), pp.243-267

35. Wade, Russian Revolution, pp.208-215

36. N.Lowe, Mastering Modern World History (4th

edn, Basingstoke, 2005), pp.347-350

37. Document 115 in Steinberg , Voices, p.283-284

No comments:

Post a Comment